This is the first in a multi-part series on construction delays by the authors

In the fast-paced world of construction, delays can pose significant challenges to project success. In this Breaking Down the Walls series we simplify the fundamentals of construction delays, providing readers with the necessary tools to proactively identify and assess delays on their own projects in Canada, and focus on the damages that are often claimed as a result of schedule delay.

PART A: Delay Claims: Understanding the Basics

Construction delay is debated on nearly every construction project in Canada, from the smallest renovations to record-breaking megaprojects. Delay leaves various stakeholders asking seemingly simple questions like: Why was the project late? Who caused it? The answers to these questions, however, can be immensely complex.

We start with analysing the concept of construction delay and identifying the steps to successfully assert or defend a delay claim. The first step is understanding what delays are.

Exactly what is “Delay”

The term “delay” in the construction context encompasses more than its ordinary grammatical meaning. Merely observing that an activity has taken place later than planned is only the first piece in a complex puzzle to ultimately determining whether there has been a “delay” to the overall project.

The Society of Construction Law’s Delay and Disruption Protocol[1] (“SCL Protocol”) provides a good starting-point in appreciating the meaning of “delay” and the importance of “delay analysis” in the construction context:

In referring to ‘delay’, the Protocol is concerned with time – work activities taking longer than planned. In large part, the focus is on delay to the completion of the works – in other words, critical delay. Hence, ‘delay’ is concerned with an analysis of time. This type of analysis is necessary to support an [extension of time] claim by the Contractor.[2]

Delay analysis is the process of assessing when and why work started later, ended later, or took longer than planned and how these delays affected the overall project schedule. This ultimately allows parties to assert and defend claims for relief, often in the form of an extension of time (“EOT”) claim.

Not all delays are treated equally, and consideration must be given to the contractual entitlement to an analysed delay. There are generally three categories of delay:

- Critical vs. Non-Critical Delay

- Excusable vs. Non-Excusable Delay

- Compensable vs. Non-Compensable Delay

Critical vs. Non-Critical delay

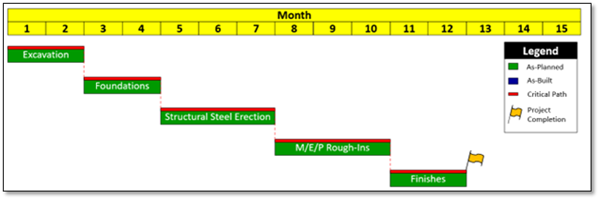

A delay analysis will most frequently employ the Critical Path Method (“CPM”), which endeavours to determine the project’s “critical path.” The critical path is the “longest chain of logically connected activities in a project schedule that, if delayed, will delay the end date of a project.”[3] Critical path delays are discrete (associated with specific events), happen chronologically (occur over time), and accumulate to the overall project delay (discrete delays add up to the total delay).[4]

All projects have a critical path, even if one is not readily identifiable from the schedule. The art of identifying critical activities and piecing together the critical path is aided by an understanding of multiple aspects of the project, including: (i) the ultimate project deliverable; (ii) the contractor plan and schedule; (iii) contractual requirements for sequencing; (iv) the logical relationship between activities; and (v) the physical or logistical constraints of the project; and (iv) how the project events actually occurred (the “as-built” schedule).

To illustrate a critical path delay, consider the example of a high-rise condominium tower. In order to construct the tower, a logical sequence of work activities is identified in the baseline (“as planned”) schedule. These activities have been simplified and are presented in Figure 1, below.